Habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement are essential components of the BBTS program. The program has identified critical areas for habitat protection and restoration/enhancement within each of the watersheds targeted for Atlantic Salmon restoration. These prioritizations include activities that will improve physical habitat, water quality and quantity, and connectivity among habitats. Atlantic Salmon have a complex life cycle, and so require the use of a wide cross section of interconnected habitats.

Atlantic Salmon use rivers and streams for part of their life cycle, which includes adult migration, spawning, juvenile rearing, and smolting. All these stages require fish to be able to both reach, and then to move, between different habitats, and therefore connectivity between habitats is essential for Atlantic Salmon and many other species of aquatic organisms to complete their life. Healthy streams have intact processes that help to maintain these diverse habitats. Most healthy river habitats are naturally dynamic and change over time. This means that rivers are continually moving and eroding both laterally, which means across the floodplain, and vertically, which means up and down the banks within their channels. These processes ensure that groundwater inputs are maintained, that woody material enters the channel to create important habitats like log jams, and that sediment and nutrients can move downstream. Many aquatic species, like fish, crayfish, and invertebrates, and terrestrial species, like amphibians and turtles, require a diversity of habitats, and by allowing natural processes like erosion, flooding, and tree falls to happen, we can help ensure this diversity of habitat types is maintained.

For adult migration upstream and smolt migration downstream, Atlantic Salmon require rivers and streams that are free of man-made obstructions, such as dams, weirs, or perched culverts. Dams can completely block upstream migration, preventing adult salmon from reaching spawning habitats, and can injure smolts travelling downstream over the dam. Many dams also have a head-pond, a slow-moving pool of water at the upstream end of the dam that can confuse smolts due to the lack of current, thereby delaying their downstream migration toward Lake Ontario. These head-ponds also often warm the water, reducing the quality of salmon habitat downstream, and prevent the movement of stream sediments, woody material, and nutrients, disrupting the natural flow of this material and causing negative changes to downstream habitats and ecological communities. Even when fishways are present at dams, they are never 100% efficient, and often are not built for non-jumping species, which are basically anything except salmon and trout. This can isolate populations above obstructions in the river from those below obstructions. Even a small jump may be impossible for most fish species. For example, in most Lake Ontario tributaries, adfluvial (fish that live in Lake Ontario and migrate to tributaries to spawn) White Suckers migrate upstream to spawn. These spawning migrations bring large quantities of food resources and nutrients that are then available for juvenile salmon and other fishes, supporting better growth rates and survival. Because White Suckers don’t jump, even dams with fishways sever this important seasonal food and resource supply. In the Lake Ontario basin, there are currently hundreds of obstructions, many of which have no functional purpose.

Juvenile Atlantic Salmon rear in rivers and streams for one to three years before they smolt and migrate downstream to Lake Ontario. Their habitats must include appropriate shelter, food, and space, and these require different components of streams, namely riffles, runs, pools, and estuaries. These requirements change across seasons, across years as the fish grow larger, and depend on the size of the stream or river. With the reduction in tree cover and increase in urbanization, many parts of streams are warmer than they used to be. Salmon and other coldwater species need connectivity so they can seek out coolwater refugia during hot summer days.

Adult salmon can actually create habitats that support juvenile productivity. Spawning adults dig spawning nests called redds. These redds are usually built in the gravel of riffles, and the act of digging alters the riffle’s slope and depth, creating more diverse micro-habitats than would have been there otherwise. Spawning salmon can also move fine sediments out of spawning gravel in a process called bioturbation, enhancing the quality of the area for other species, like other fish and benthic macroinvertebrates which also act as food resources for juvenile salmon.

The habitat team identifies and addresses the major factors limiting the life history stages of Atlantic Salmon as needed. To help achieve habitat protection and restoration/enhancement, the habitat team works with landowners, MNRF, DFO, conservation authorities, municipalities, non-government organizations such as Ontario Streams and Trout Unlimited Canada, and the public.

The core types of projects the BBTS program works on are:

- Modification, by-pass, or removal of online dams and ponds to re-establish natural channels, decrease stream temperatures, and allow fish passage.

- Tree planting in riparian areas to stabilize banks and decrease sedimentation and water temperature.

- Cattle fencing and alternate watering systems to prevent riparian grazing, erosion, and in-stream habitat destruction.

- Bank stabilization projects to minimize erosion and sedimentation of spawning and nursery areas.

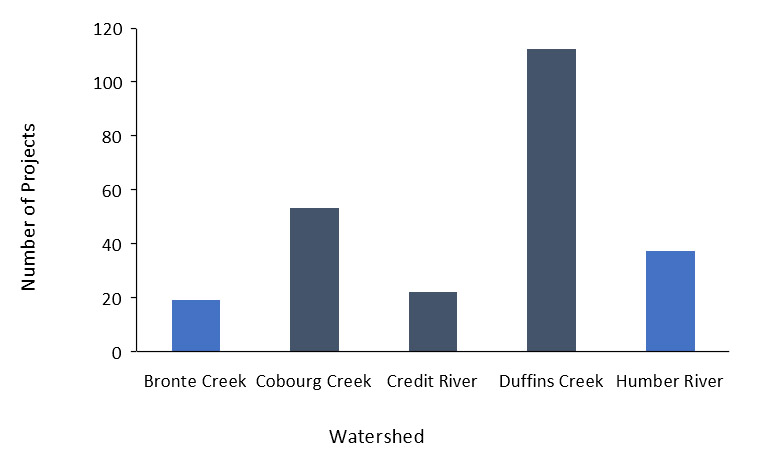

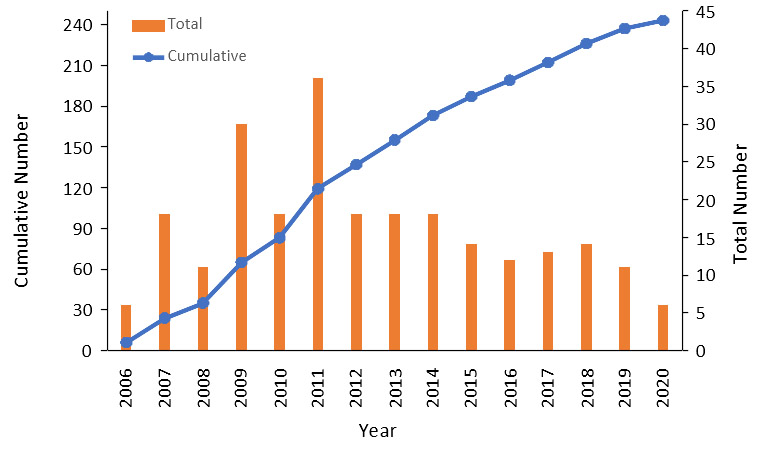

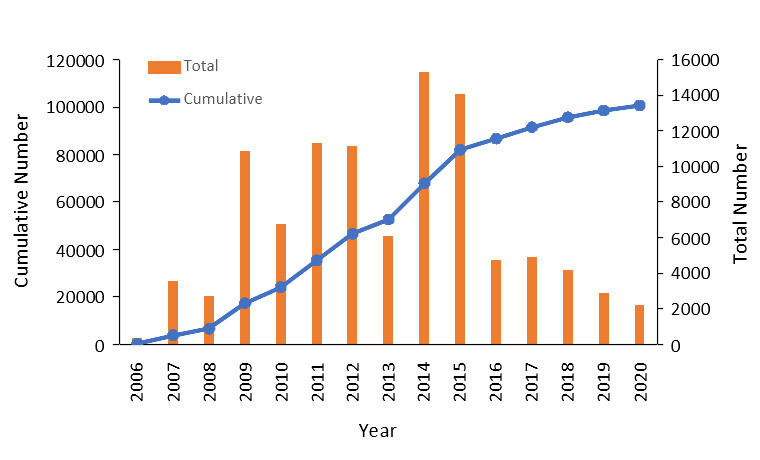

The program currently conducts habitat projects in five watersheds (Figure 1). Since the inception of the program, 243 projects have been completed (Figure 2), and over 100,000 native trees and shrubs have been planted (Figure 3). Projects have consisted of a wide cross-section of types, including refuge cleanup, bank stabilization, barrier mitigation and removal, thermal pollution mitigation, in-stream habitat placement, and tree and shrub planting. These projects all cumulatively increase valuable coldwater fisheries habitat, supporting various life stages and processes (e.g. spawning, juvenile migration) for Atlantic Salmon, but also for a suite of other intolerant aquatic species that require clean, cold water, and good physical habitat. Additionally, all projects support overall biodiversity at each site, enhancing habitat for both aquatic and terrestrial species. For all tree and shrub planting, these also serve to mitigate climate change and enhance carbon sequestration. Many projects involve the support of volunteers, and 8,337 volunteers have supported habitat projects since 2006, with upwards of 950 volunteers in the most active years. All habitat projects over the last five years have been guided by the LOASRP Phase III Habitat Plan, which prioritizes habitat projects within each targeted watershed. The next phase of the habitat plan is currently in preparation to support planning and implementation over the next five years of the program.

Figure 1: Habitat projects within target watersheds from 2006-2020

Dark blue bars are the three primary watersheds, light blue bars are the two secondary watersheds.

Figure 2. Cumulative number and total number of habitat projects completed across all watersheds.

Figure 3. Cumulative number and total number of native trees and shrubs planted across all watersheds.

Bring Back the Salmon Newsletter

Program Partners and Supporters

Contact Us

1-800-263-OFAH (6324) ext. 237

PO Box 2800

Peterborough, Ontario

K9J 8L5